An Eskimo Vocabulary for Arctic Explorers

Eskimaux and English Vocabulary, for the Use of the Arctic Expedition (London: John Murray, 1850).

At first glance an unassuming little book bound in simple black cloth, the unexpected title – “Eskimaux Vocabulary / For the Use of the Arctic Expedition” – boldly printed in gilt to the front cover, quickly catches the eye and the imagination.

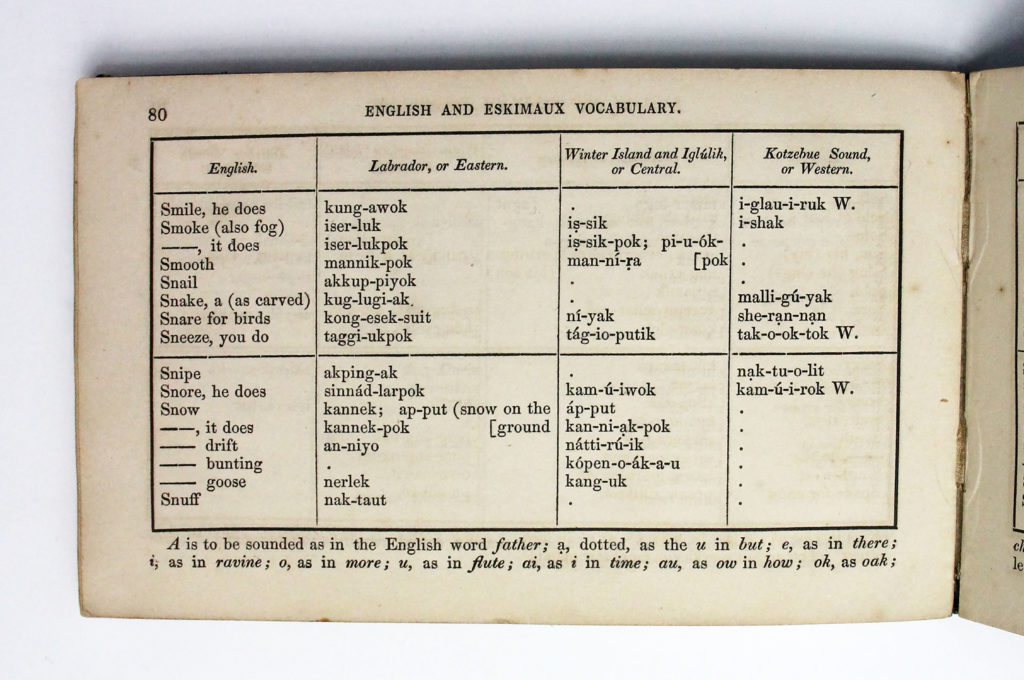

Published in London in 1850, it was designed as a field guide to Inuit languages for European Arctic explorers, enabling the translation of useful phrases back and forth between English and what it defines as three categories of native dialect: “Labrador, or Eastern”, “Winter Island and Iglúlik, or Central”, and “Kotzebue Sound, or Western”.

In introducing the guide, its author, John Washington (1800-1863), a Royal Navy officer and founding member of the Royal Geographical Society of London, describes the Inuit languages as “graceful and energetic”, praising the “strength and brevity” of expression which resulted from their tendency to blend multiple words. He also notes how they “abound in words expressive of common objects”, for example animals, the natural landscape and weather, through which they can distinguish “slight shades of difference” via the use of specific terms.

Despite, however, the clichéd claim that Eskimos have more than fifty different words for ‘snow’, this guide offers only a couple. Indeed, its focus was essentially practical, aiming to condense previous tomes – “of little use…for the daily requirements of parties…in boats or on land expeditions” – into a handy pocket guide, furnishing “every officer and leading man in the Arctic expeditions with a book of ready reference that he can carry in his pocket without inconvenience”.

A typical page from the Vocabulary, showing the entry for ‘snow’.

In addition to translating many hundreds of key words, the guide contains several specimen dialogues with titles including “On first meeting with natives” and “Dialogue with a sick man”. Through these, an explorer could learn how to translate phrases such as “I want to buy twelve good dogs”, “We are going to travel over the ice / Will you go with us as a guide?”, and “Do you catch many seals? / Show us how you catch them”. It also includes tips on conversing with Inuit peoples, noting how they “make much use of winks and nods”, as well as awkwardly advising perhaps usually reserved British naval officers that in “close quarters rubbing noses is the most approved mode of salutation”.

The central purpose of the guide was, however, even more particular than simply assisting Arctic exploration – it was created with the explicit aim of aiding one of the most famous rescue missions of the nineteenth century.

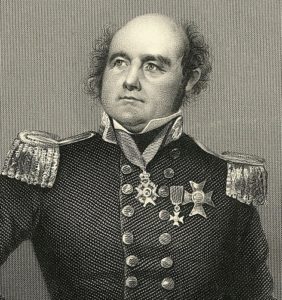

Sir John Franklin

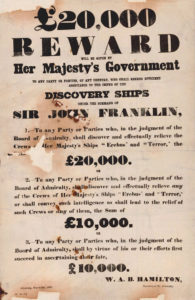

In May 1845, Sir John Franklin, a renowned explorer and veteran of three previous Arctic expeditions, set out with two ships and 134 crew to map the last unnavigated section of the Northwest Passage through northern Canada. On 26th July they were sighted for the final time by a European vessel in Baffin Bay. Two years then passed with no word from the expedition, leading Franklin’s wife, Lady Jane Franklin, to repeatedly urge the British government to send a search party. After a third year elapsed, and with the expedition only carrying provisions for that length of time, the Admiralty finally agreed, offering a staggering £20,000 reward for locating Franklin and his men. The size of the reward (about £1.6 million today) and Franklin’s fame led to widespread public interest and numerous expeditions, with the search becoming something of a national crusade.

Poster offering a reward for help in finding Franklin’s lost expedition.

Washington hoped that his Vocabulary – “compiled for the use of the Arctic Expeditions fitted out at the expense of the British Government to carry relief to Sir John Franklin and his companions” – would aid in bringing “the joyful intelligence” of their safety. He was encouraged in this thought by previous expeditions which had experienced much helpful “intercourse…with the natives of the north-western coast”. He thus included in his guide specific lines to be recited to any Inuit encountered: “We are in search of two English ships / Which have been five years in the ice / Have you heard anything of such ships? / Make it known among all the Eskimos or Innuit / That the Queen of England will give a large reward / To any of the Innuit who will bring news of them”.

It certainly appears that the guide was actively used in the search for Franklin. Peter Sutherland, a member of two such expeditions during 1850-51, gave it a notable mention, declaring that only through using that “excellent vocabulary”, had they managed to make themselves “tolerably well understood” (albeit still complaining that the replies they received were “too hastily made, and far too voluminous to be comprehended”).

Washington’s motivations were indeed ultimately vindicated when, in 1854, it was through conversing with Inuit hunters that the Scottish explorer John Rae became the first to learn of the Franklin expedition’s fate – how both ships had become icebound, and how the men, after attempting to reach safety on foot, had succumbed to cold, with some even resorting to cannibalism.

Whether Rae himself used Washington’s Vocabulary at any point is unknown. Nevertheless, this compact field guide, designed for easing the interaction of two alien cultures, would have been an essential piece of kit, stuffed into the bags of many nineteenth-century polar explorers. With such a specific purpose, few copies would have originally been printed, and most that were have not endured what would have likely been a rough-and-ready life, making this copy a genuinely rare survivor and a fascinating piece of Arctic history.