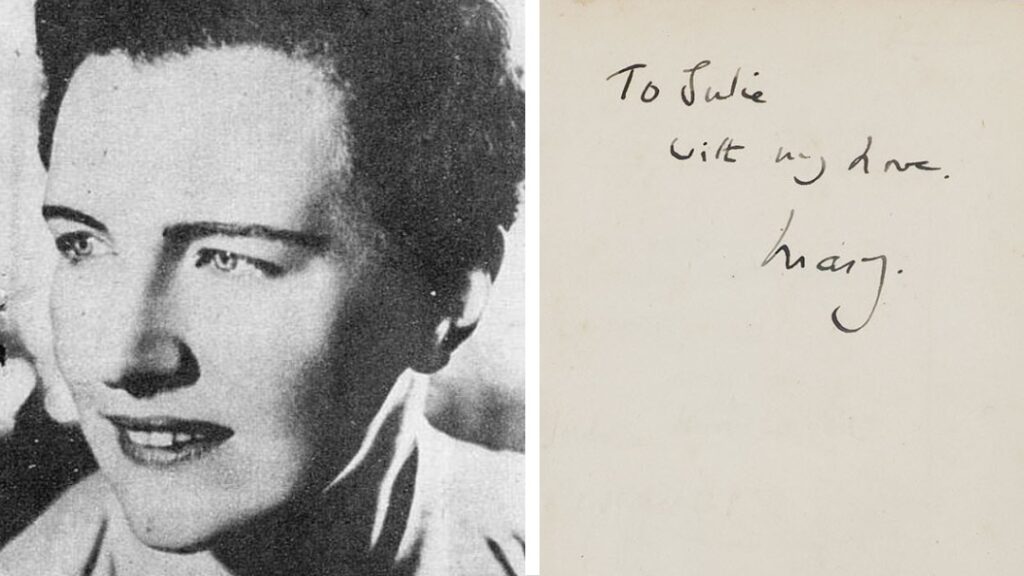

From the Library of Mary Renault

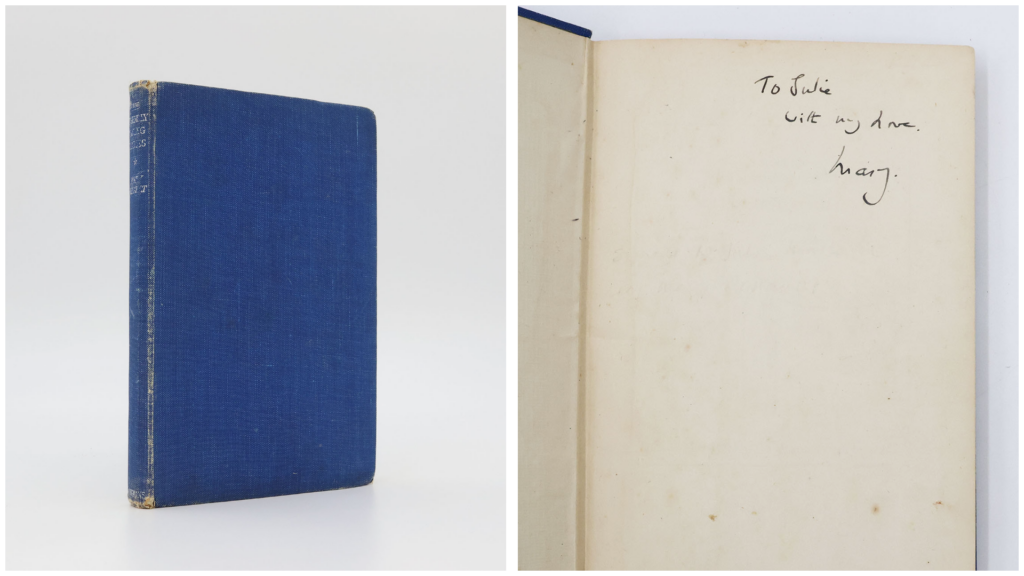

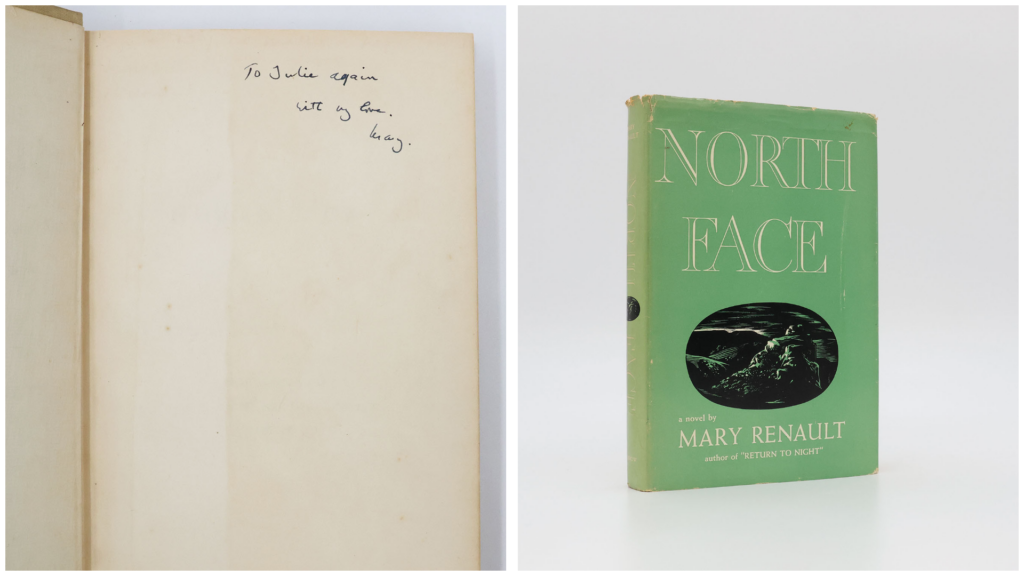

We have recently acquired a wonderful collection of four books from the library of Mary Renault (pen name of Eileen Mary Challans), an early pioneer of gay fiction whose later historical novels have become some of the best loved works to be set in Ancient Greece. Two of the books in this collection, ‘The Friendly Young Ladies‘ and ‘North Face’, contemporary novels written by Renault, are astounding association copies, inscribed by Renault to her life partner Julie Mullard.

Renault was born in 1905 in Forest Gate, London, to Frank Challans, a doctor, and Clementine Baxter, the daughter of a dentist. She was brought up in a comfortable middle-class neighbourhood suffused with a culture of respectability, which would later inform the backdrop of a number of her contemporary novels, enduring the subtle social criticism that supports her more foregrounded exploration of the human psyche and interpersonal relationships.

Much to her mother’s disappointment, Renault was a bookish tomboy who occupied herself with literature (she had read all of Plato by the time she left school) and early endeavours in writing fiction and poetry, the latter of which took the form of medieval pastiches. Renault’s parents had a strained relationship and their constant arguing left little remaining attention for to their eldest daughter. They were blind to her strengths and neglected her education, a wound Renault would carry throughout her life. Fortunately, an aunt came to the rescue and paid for Renault to attend boarding school and then to study at St. Hughes’ College, Oxford, which was then a relatively new women’s college.

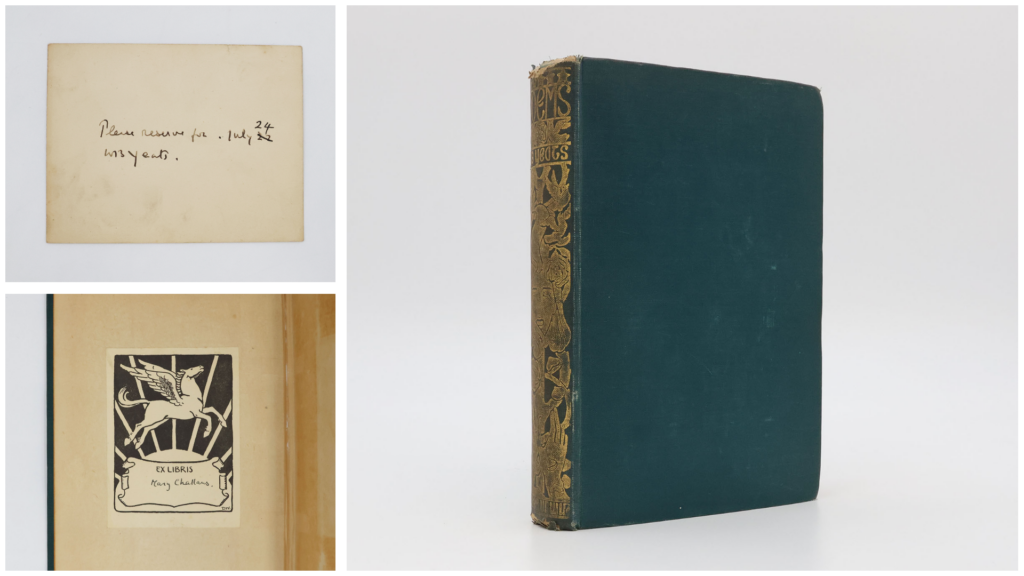

While at St. Hughes’ Renault was taught and influenced by J. R. R. Tolkien and Joan Evans (who also owned the accommodation Renault lived in), the sister of Arthur Evans, the archaeologist who excavated and (controversially) reconstructed the Minoan palace of Knossos on Crete, which would become the setting of Renault’s 1958 novel ‘The King Must Die’. One of our books from her library dates from this period of her life, a copy of W. B. Yeats’ ‘Poems’ (1927), which curiously has a card, signed by Yeats, loosely laid in.

Upon graduating in 1928 Renault was expected either to marry or become a teacher, fates that she firmly refused. Instead, she attempted to survive on a meagre allowance and the income from a string of low-paid jobs, which resulted in malnutrition and eventually rheumatic fever, requiring her to convalesce, begrudgingly, at her parents’ house for over a year. Once recovered, desperate for freedom, Renault embarked on a solo walking holiday in 1933, during which she found herself once again in Oxford. There she impulsively walked into a hospital, Radcliffe Infirmary, and asked to become a nurse, a decision that would prove to have a profound impact on both her literary career and personal life.

Whilst training at the infirmary Renault wrote as much as she could in her scant spare time, and many of her early novels draw directly on her nursing experience, being hospital romances like her first novel, ‘Purposes of Love’ (1939), or involving characters who are nurses or doctors, as in ‘The Friendly Young Ladies’ (1944). During this period Renault also formed a close relationship with a fellow trainee nurse, Julie Mullard, who would become her partner for the rest of her life, and her literary executor after her death in 1983. Our copies of Renault’s ‘The Friendly Young Ladies’ and ‘North Face’ (1948) are both movingly inscribed ‘with my love’ to Mullard from Renault.

Despite homosexual activity between men being criminalised in the UK until 1967 (female homosexuality had never been criminalised) and contemporary books with homosexual themes facing suppression, such as Radclyffe Hall’s lesbian novel, ‘The Well of Loneliness’ (1928), which was withdrawn following an obscenity trial, Renault included homosexual and bisexual relationships and characters in her novels, if in an indirect and veiled manner, from the beginning of her writing career. Her first published book, ‘Purposes of Love’, is a heterosexual love story about the relationship between a student nurse, Vivian, and a pathologist, Mic. However, the two are first linked by their connection with Jan, Vivian’s brother, who Mic has feelings for. Furthermore, one of Vivian’s friends, a fellow nurse, lives openly as a lesbian. Renault’s third book, ‘The Friendly Young Ladies’, follows a teenage girl who escapes her parents’ mundane middle-class world to live on a houseboat with her bohemian sister Leo, a writer in an obfuscated lesbian relationship with a nurse, a situation notably similar to Renault’s own. Renault purportedly wrote ‘The Friendly Young Ladies’ as a light and witty response to the bleak portrayal of lesbian life in Hall’s ‘The Well of Loneliness’, a book that Renault and Mullard found merely amusing.

Even when dealing with purely heterosexual love stories, Renault maintains the themes found in her homosexual romances of complex, unconventional relationships that generate a multitude of mixed emotions in their protagonists and draw scrutiny from the outside world. ‘Return to Night’ (1947) is about a female doctor in her thirties who enters a challenging relationship with a patient, a man over a decade her junior who lives under the control of his manipulative mother. In ‘North Face’ a man who is reeling from divorce and grief meets a woman in a Devon guesthouse who is dealing with her feelings around the death of her fighter pilot fiancé who she was not sexually attracted to, and the pair slowly fall in love under the judgemental eyes of the other guests.

Renault and Mullard relocated to Durban in South Africa in 1948 after Renault had been awarded $150,000 by MGM Studios for ‘Return to Night’. Here Renault was among the first to join the Black Sash, a white women’s organisation formed to oppose apartheid, with whom Renault would attend protests. Despite political tension, South Africa offered a more liberal attitude to homosexuality than the repressive culture of mid-century Britain, and it was here that Renault felt able to write ‘The Charioteer’ (1953), her final contemporary novel and her first to directly address homosexual relationships. Set during World War II, it tells the story of Laurie, a young soldier who has been injured at Dunkirk and sent to a British hospital, where he falls in love with Andrew, a hospital orderly and conscientious objector who has not yet experienced awareness of his own sexuality, and the two form an intense, chaste relationship. Later Laurie is reintroduced to Ralph, a former schoolmate who was expelled for sexual activity with another boy, now an experienced and self-assured member of the nearby city’s underground gay culture. The book’s title comes from Plato’s application of love to his Charioteer allegory from Phaedrus, in which the lover’s soul steers two horses, one that is innocent and obedient and another that is lustful and untamed, a testament to the love of Ancient Greek history and literature that Renault had nursed since childhood.

Renault and Mullard travelled together through Greece on an extensive research trip before Renault’s first historical novel, ‘The Last of the Wine’ (1956), a book about the love between two young Athenian men during the Peloponnesian war, was published. It would be the first of eight successful novels set in Ancient Greece, featuring figures like Alexander the Great, Socrates and Plato. Many of these historical novels prominently featured romance between male characters, and the ancient setting allowed Renault to write about these relationships in purely human and emotional terms, free from the ideological weight of the heated contemporary political and social topic of gay rights that was slowly unfolding throughout her writing career. While Renault was steadily gaining a cult gay following, the historical setting of her novels also rendered their homosexual content palatable to the still conservative mainstream British public by the fictional separation of millennia.

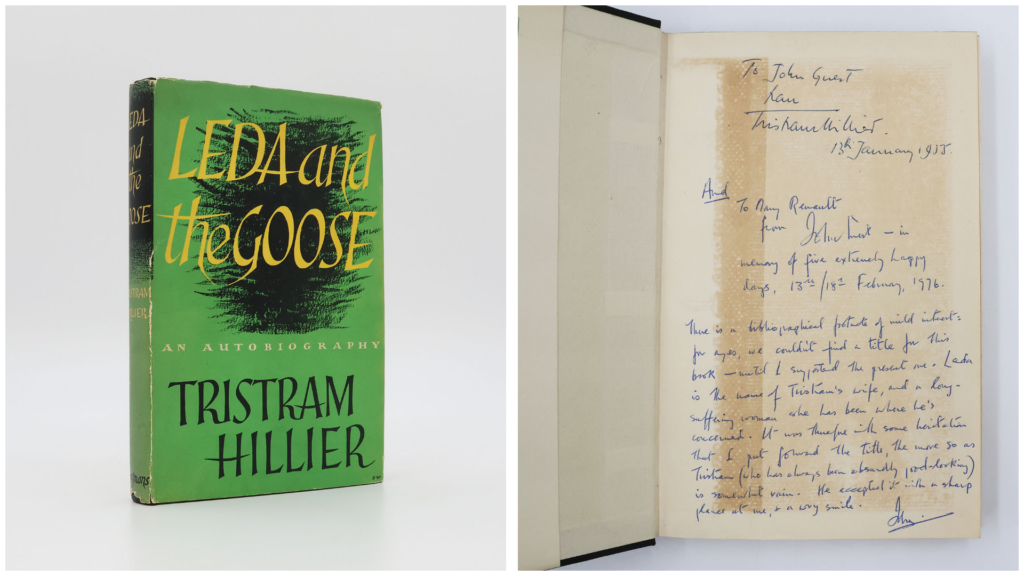

John Guest of Longman’s became Renault’s editor for ‘The Charioteer’ and remained so for the rest of her career. One item from Renault’s library is a copy of ‘Leda and the Goose’ (1954), the autobiography of the British surrealist artist Tristram Hillier, inscribed first by Hillier to Guest in 1955, and again by Guest to Renault to commemorate his visiting her for five days at her house in Cape Town in February 1976. Guest wrote down his memories of the trip, part of which was published in Books and Bookmen in 1984, describing Renault’s eclectic décor, crowded garden and lively social life furnished with characters from the theatre scene. One anecdote tells of a metal statue of Hermes that Renault kept in her garden – she had commissioned a metalworker to remove its fig leaf and fill the empty space with a new phallus that turned out to be comically over-sized. Guest had previously enjoyed a stay in Athens with Renault in 1962, during which he recalled her suggesting that they and their companions go to a local gay night club, where she was treated like a guest of honour by staff and revellers.

Renault died of lung cancer in Cape Town in 1983 at the age of 78, having earned herself a significant position in the canon of gay literature, helped to normalise homosexual themes in English literature, and become a veritable icon of Ancient Greek historical fiction. This small but fantastic collection provides a fascinating glimpse into her world; the two inscribed association copies offer a touching connection to her relationship with the most significant figure in her life, while the two books by other authors serve as artefacts of two very different periods in the eccentric and vivid life of a groundbreaking writer and remarkable character.

Bibliography:

Beale, S. R. (2015). ‘Mary Renault’s The Charioteer is an antidote to shame’, The Guardian, 15 November. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/nov/15/mary-renault-charioteer-simon-russell-beale

Jordison, S. (2014). ‘Mary Renault’s Alexander: history and fiction both’, The Guardian, 21 August. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2014/aug/21/mary-renault-alexander

The Mary Renault Society (2025). Who is Mary Renault? Available at: https://www.maryrenaultsociety.org/who-is-mary-renault.html

Sweetman, S. (1993) Mary Renault: A Biography. London: Chatto and Windus.