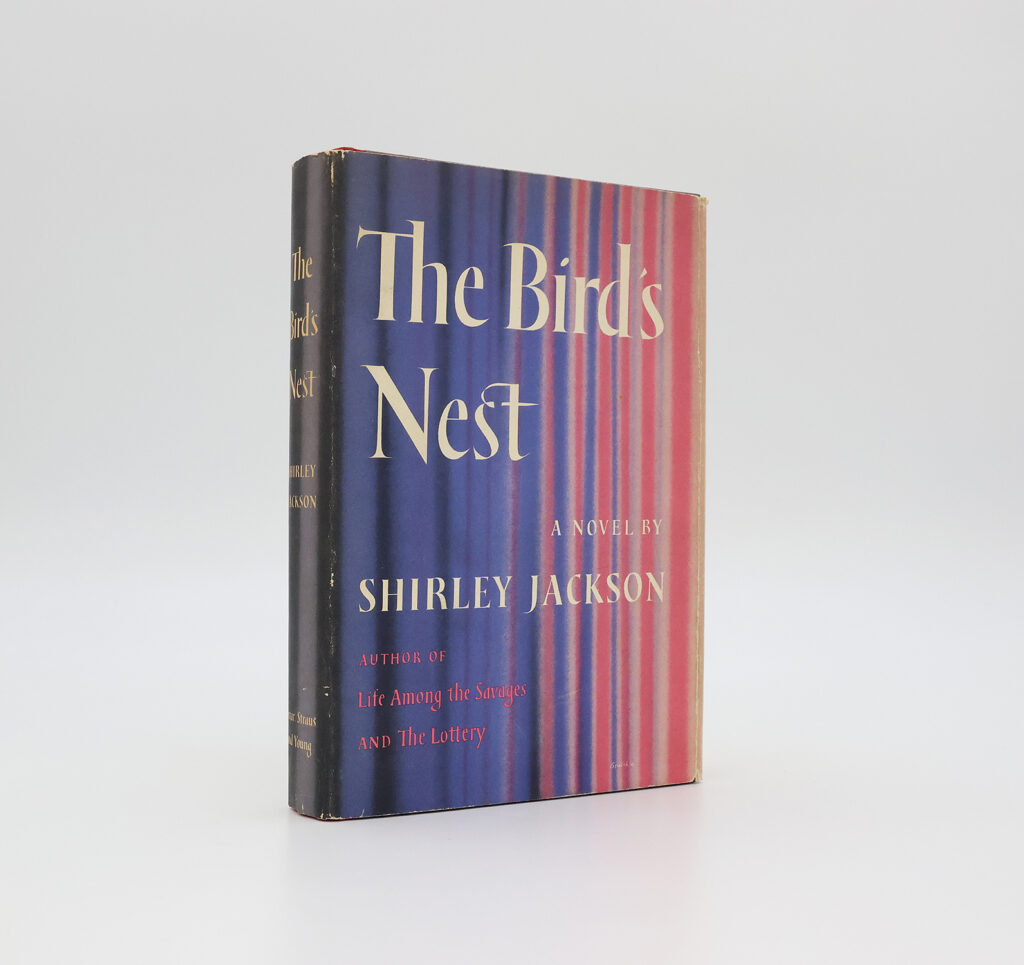

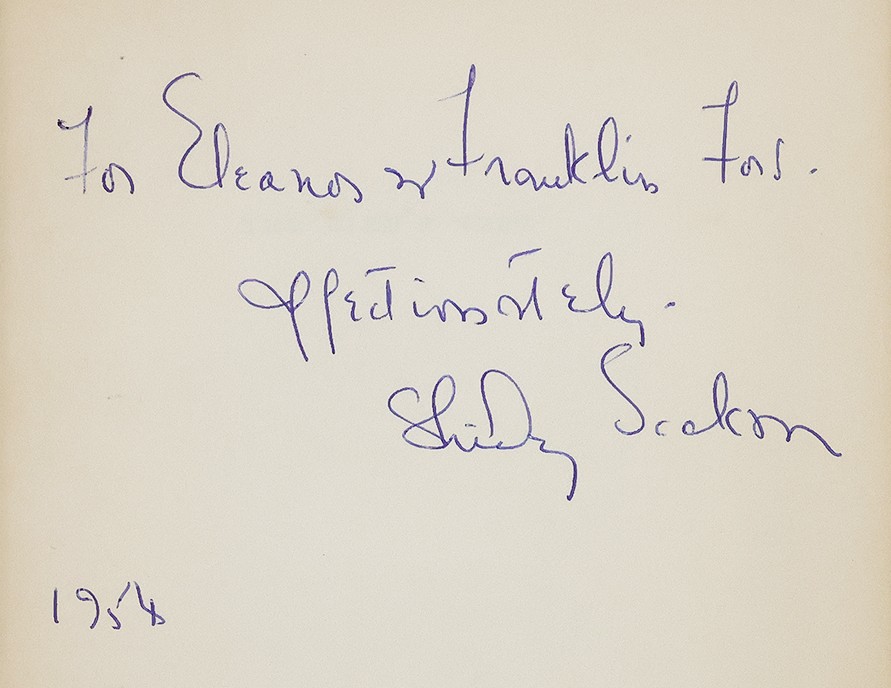

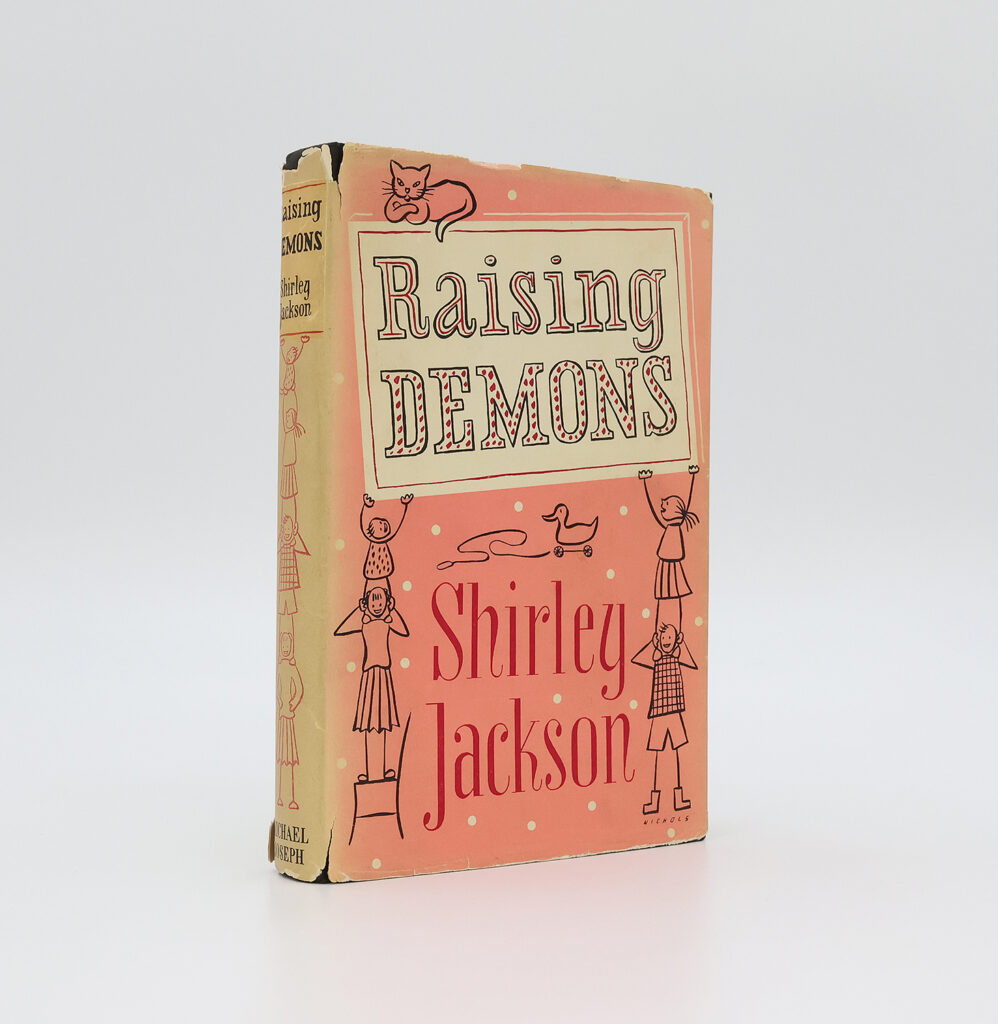

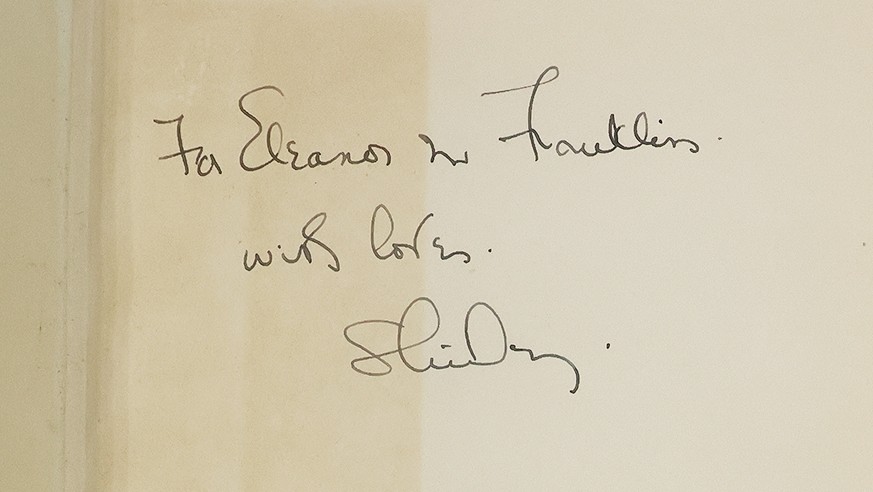

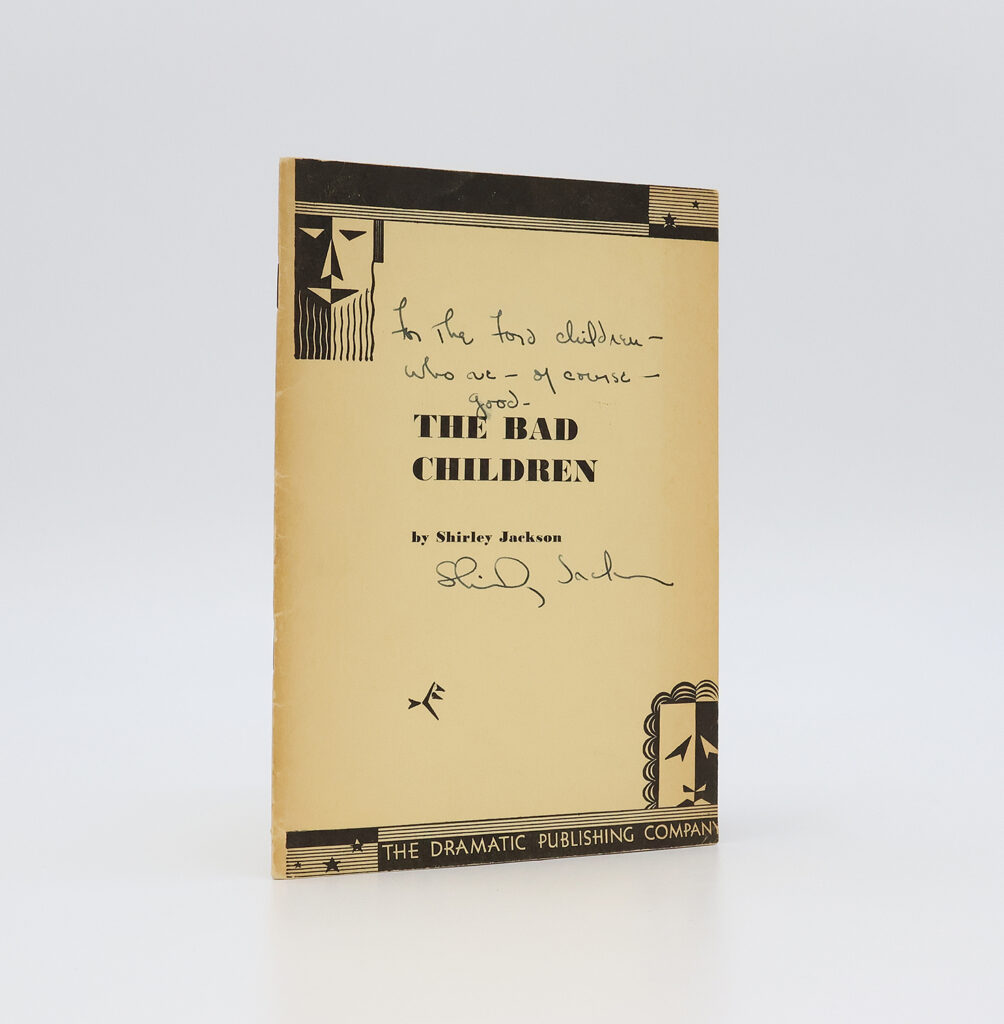

The gothic is currently haunting our screens and imaginations, with dark, dramatic films like Robert Eggers’ ‘Nosferatu’ (2024), Guillermo del Toro’s ‘Frankenstein’ (2025) and Emerald Fennel’s highly anticipated ‘Wuthering Heights’ (2026) drawing avid audiences. This curious genre is central to the work of the American writer Shirley Jackson, a personal favourite of mine and the author of some of our most exciting recent acquisitions, including exceedingly rare inscribed copies of ‘The Bird’s Nest’, ‘Raising Demons’ and the scarce children’s play, ‘The Bad Children’.

While gothic literature’s most recognisable imagery lies in particularly monstrous and fantastical figures that are repeatedly revisited, such as Bram Stoker’s vampiric Count Dracula and Mary Shelley’s reanimated ‘monster’, a quieter but just as vital archetype has also enjoyed a long history within the gothic tradition. The ‘domestic gothic’ explores the horror and mystery found within and around the realm of the home, the family and the domestic sphere, often centering on its female inhabitants, and can be traced through Emily Bronte’s ‘Wuthering Heights’, Mary Shelley’s ‘Mathilde’, Charles Dickens’ ‘Great Expectations’ and Daphne du Maurier’s ‘Rebecca’. It flourishes throughout Jackson’s work, providing a perfect vehicle for conveying her female characters’ feelings and experiences.

The house itself is a vital component of much of Jackson’s work, though it takes on multiple attitudes; variously it is malevolent, a sanctuary, or an uncomfortable idea that cannot be ignored. In Jackson’s final novel, ‘We Have Always Lived in the Castle’, the Blackwood sisters Merricat and Constance become something like prisoners in their looming, tomb-like house, the almost animistic ‘castle’ of the title, yet within the house they build their own weird idyll, screened from the horrors of the outside world. On one hand Constance embodies the idealised 1950s vision of a housewife, happily cooking elaborate meals and keeping her domain spotlessly clean, yet she is also shown as undeniably odd in retreating from society and stubbornly ignoring reality. In a novel with a similarly enigmatic and even more convincingly sentient house we join Eleanor, the timid and unformed protagonist of ‘The Haunting of Hill House’, following the death of her overbearing mother to whom she has been a carer her whole adult life. Just as she finally escapes the prison of one house, she is irresistibly drawn to and captured by another, inviting connections between the image of the haunted house and the haunted mind.

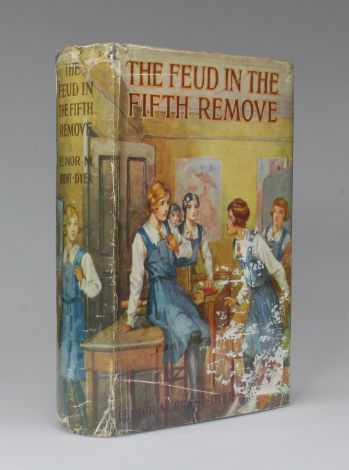

In ‘Hangsaman’, the central character, Natalie, succeeds in escaping the symbolic domestic world represented by her family’s house, but must struggle through madness as she attempts to find her way, not only as a child transforming into an adult, but as a woman stepping into an academic world that has only recently and barely made itself receptive to women. The other significant female characters, Natalie’s mother, a sorrowful and caring but ultimately underappreciated housewife, and Mrs. Langdon, a young, disappointed and increasingly manic faculty wife, are both characterised primarily through their complex relationships with their domestic roles. The three women feel almost like three fragmented parts of a single woman, and it is notable that Jackson herself experienced significant aspects of each of their lives.

The concept of the fragmentation of the self had long been of interest to Jackson, who in her teenage years gave names to her different moods. She explores this idea at length in ‘The Bird’s Nest’, a novel about a young woman with dissociative identity disorder. In this instance, instead of the realm of academia, Elizabeth has recently entered the world of work, though passively and under the insistence of her aunt. Like her personality, her home life is broken apart: her parents are dead and, despite living with her aunt, she has no domestic anchor to rely on, as Merricat has Constance and Natalie has her mother, yet she has no drive to escape as Eleanor does. Through her doctor’s notes we witness his judgement of each of Elizabeth’s personalities, often centered around feminine attractiveness, deeming this one slow and unattractive, that one pretty and charming, another rude and frightening, emphasising the way that an individual’s personality may be curated to pacify or rebel against people or systems, and how this tendency may be manipulated by the world around them.

Whether a minor or major theme, the inclusion of the domestic is common to virtually all of Jackson’s works. Some of her most domestically centered writing, however, is found in her two memoirs, ‘Life Among the Savages’ and ‘Raising Demons’, which themselves curate a vision of Jackson’s own life as a mother and wife. While they fall firmly within the family comedy genre rather than her usual gothic fiction, a nod to the occult can be found in the titles themselves, while her infrequent and subtle yet sharp depictions of tension between wife and husband, and selfhood and motherhood, are reminiscent of the dark edge of her fiction by virtue of their unflinching clarity.

Interestingly, like a single shard of Elizabeth’s personality, Jackson here exemplifies the need and desire to display just one side of a personality. ‘Savages’ followed a lukewarm reception to ‘Hangsaman’, and was pieced together from short stories she had sold to popular magazines such as ‘Good Housekeeping’ and ‘Woman’s Home Companion’, which delivered a welcome reliable stream of income that foretold the even greater commercial success of the book and its sequel. Early drafts show that Jackson softened moments of pain and distress for the final manuscript, shaping a character that was true to Jackson’s domestic life, but only presented the parts that would be relatable and uplifting to the reader. Her depiction of herself as an eccentric and hapless homemaker rebels against the image of the multi-tasking, perfectly primped housewife that was rife in advertising and media during the mid-twentieth-century’s cultural backlash against the increase of women in traditionally male-dominated fields. However, mention of her creative life and career are conspicuously absent, despite the fact that Jackson’s work paid for the majority of the family’s bills and is evidenced by the very existence of the memoirs themselves.

Jackson’s explicit portrayal of herself as wife and mother in relation to her implicit disguising of her nevertheless undeniable life as an artist and professional writer reflects the reason why her use of the domestic gothic genre to explore female characters and experiences is so effective, particularly at the time at which she was living and writing. Like Frankenstein’s monster, made of a patchwork of disparate parts, or Count Dracula, who is neither truly alive nor truly dead, Jackson’s female characters claw futilely at a defined sense of self from within a dense limbo of womanhood that remains opaque whether they meet the criteria of a traditional domestic woman, reject or escape the domestic sphere, or rewrite their own version of domestic life. Though strange, vast and complex, her characters are inevitably cajoled and squashed into the categories of housewife or new woman, while always failing to both live up to and be constrained by the simplistic ideal of either, existing at the point of tension between many different worlds, demands and identities, where the uncanny resides.

- Bibliography:

- Franklin, R. (2017) Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation.

- Jackson, S. (2013) Hangsaman. London: Penguin.

- Jackson, S. (1957) Raising Demons. London: Michael Joseph.

- Jackson, S. (2014) The Bird’s Nest. London: Penguin.

- Jackson, S. (2009) The Haunting of Hill House. London: Penguin.

- Jackson, S. (2009) We Have Always Lived in the Castle. London: Penguin.

We are delighted to host the author and Tartarus Press co-founder R.B. Russell and the South Yorkshire press ‘And Other Stories’ for the launch of

We are delighted to host the author and Tartarus Press co-founder R.B. Russell and the South Yorkshire press ‘And Other Stories’ for the launch of